Point of impact

Concussions sideline players as sports struggle to adapt

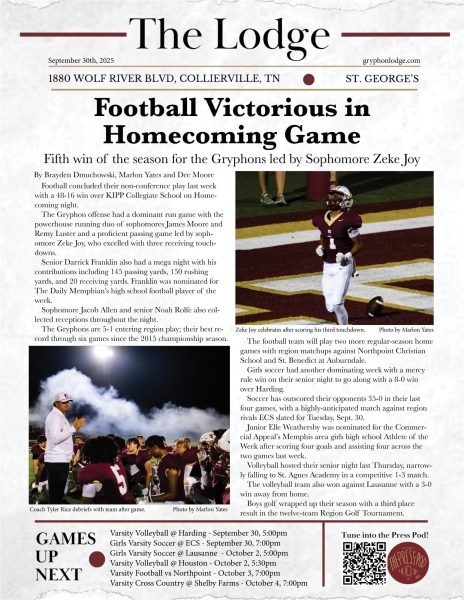

On May 7, 2016, the St. George’s women’s lacrosse team is playing in the state Elite 8. Only five seconds are left in the quarter-final game for girls’ lacrosse. St. George’s is up by several points. Fans on both sides can be heard screaming their support.

Suddenly, two players swing at St. George’s defender Emily Grace Rodgers, catching her head between their metal sticks. Rodgers is thrown to the ground by the force of the impact, hitting her head once more.

Inside Rodgers’ head, the impact is strong enough to cause her brain to collide into the side of her skull, resulting in bruising, broken blood vessels and perhaps even nerve damage to the brain.

Rodgers has just received a mild traumatic brain injury, more commonly known as a concussion. Rodgers remains on the ground, completely unconscious, for almost three minutes. When she regains consciousness, she has lost her vision.

“They had to carry me off the field,” Rodgers said. “Once I got off the field, I was throwing up everywhere. It was disgusting.”

Since the game is in Nashville, the ambulance takes her to Vanderbilt Pediatrics, where she stays overnight. There, the doctors diagnose her with a concussion.

* * *

Rodgers’ case is an example of the 25 percent of sports-related concussions caused by aggressive or illegal play, but the majority are received during the course of regular play. And their numbers are only increasing. According to a recent study of emergency room visits, sports-related concussions for teens ages 14 through 19 more than tripled from 1997 to 2007.

After the enactment of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) legislation that requires student athletes, coaches, parents and trainers to be informed on the risks and symptoms of concussions, the percent of total injuries in high school sports that were concussions increased from 10 percent to over 20 percent. In girls’ soccer, the percentage of concussions among total injuries increased from 13 percent to over 27 percent, according to a paper published in 2017 from the annual meeting of the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

It is difficult to pinpoint an exact cause for this increase, but growing awareness about the dangers of concussions is certainly playing a part.

One reflection of that increased awareness is the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association’s concussion policy, which reads that “Any player who exhibits signs, symptoms or behaviors consistent with a concussion (such as loss of consciousness, headache, dizziness, confusion or balance problems) shall be immediately removed from the game and shall not return to play until cleared by an appropriate health-care professional.”

Another is St. George’s own policy, which quotes the TSSAA’s language directly and states that students with severe concussions are required to be cleared by a Clinical Neuropsychologist before returning to play. St. George’s employs two certified athletic trainers who, according to the St. George’s website, “manage all concussions and athletic injuries” and use ImPACT testing to assess students for concussions.

“We have to do online testing. The NAT requires it, and the CDC also requires us to take an online quiz,” Ms. Tina Cole said, one of the two athletic trainers at St. George’s. “They do require all coaches and athletes to sign off on the continuing education of concussions.”

* * *

Despite these preventatives, concussions have still had a large impact on the St. George’s community.

In a survey sent by the Lodge in early March, 28.2 percent of the 163 respondents reported that they believed they had received a concussion while playing a sport, while another 9.8 percent thought that it was possible they had received a concussion.

Out of the 28 percent, 31.1 percent of students had received a concussion while playing soccer, while 29.5 percent had received a concussion playing football.

While studies differ on how they track the rate of concussions in each sport, the five sports mentioned most frequently as having the highest concussion rates are football, women’s soccer, men’s lacrosse, women’s basketball and men’s ice hockey. Of these, the risks of football are perhaps the most widely known as the 2015 movie “Concussion” brought attention to the dangers of head injuries in football by telling the story of Dr. Bennett Omalu, who first identified chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

CTE is a progressive degenerative brain disease most commonly found in athletes, caused by repeated brain trauma. The effects of CTE include impulse control problems, aggression, depression and eventually progressive dementia. CTE was found in 87 out of 91 brains of deceased NFL players in a study conducted by Boston University. A study done by Purdue University found football players are not only at risk of receiving a concussion by a single blow to the head, but that they can also get concussions through repeated contact.

St. George’s alumnus Austin Grisham knows those risks all too well. He played safety while he was in high school and said he received more than 12 concussions from sports during middle school and high school.

“I stopped counting them. I really don’t know the exact number,” Grisham said.

During the state championship game in 2011, Grisham received what he perceived as concussion-level hits to the head on three separate occasions. Two of the three times, Grisham tackled with his head down, which resulted in a blow to the top of his head.

“[It] ruined my life. Not ruined my life, but affected it greatly. I couldn’t go to school for several months,” Grisham said. “I have effects everyday, and I will have them the rest of my life.”

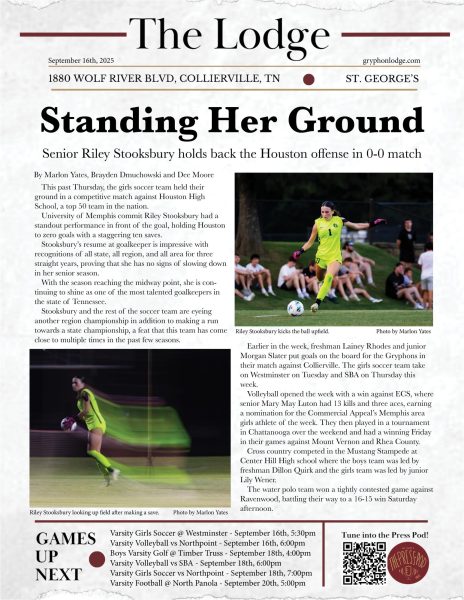

The risks of soccer are far less widely discussed, though they are just as significant, particularly for women.

Sydney Spadafora, a St. George’s alumna and freshman on the Carson Newman women’s soccer team, said she has received multiple concussions during her soccer career.

In women’s soccer, players are at risk of sustaining a concussion through player-to-player contact, heading the ball or hitting their head against the ground or goal posts. A study published by JAMA Pediatrics found that 52 percent of concussions in girls’ soccer were caused by player-to-player contact.

“I’ve had four in three to four years, and my first three were within a year from each other,” Spadafora said. Her most recent concussion put her out for six months.

“At the time, I couldn’t remember what had happened. My mood changed tremendously,” Spadafora said.

According to Dr. Brandon Baughman, who is board certified in Clinical Neuropsychology and an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine, mood swings like Spadafora’s are not abnormal.

“People who have concussions may get more emotional than normal,” Dr. Baughman said. “They may get depressed. They may get real stressed out. They may get more irritable and frustrated above and beyond any kind of normal.”

Mood changes aren’t the only effect of concussions. Spadafora also experiences memory problems now because of her concussions.

“Trying to remember to do simple tasks, when someone asks me to do it later on in the day, [I] completely forget to do it,” Spadafora said. “I used to not be able to drive at night. It was really hard. I’m learning how to work with that.”

* * *

Sports organizations have struggled to adapt to the rising awareness of concussion risks, making changes to their rules, teaching new techniques, and adopting new headgear, though it remains to be seen how effective those changes will be.

The governing body for youth football, USA Football, has begun to implement new rules, including a shortened field and matching players of equal size, in select youth football programs across the nation.

Youth soccer organizations have made it against the rules for players 11 and under to head the ball and limited the amount of time older players can practice the skill.

The introduction of padded headbands is a different approach designed to try and reduce the number of concussions in soccer. While these are supposed to prevent concussions, some argue that they might actually increase the chance of receiving a concussion.

“Often times, when the students that I know who’ve worn [soccer headgear] put [it] on, they feel like they can play a lot more aggressive and loose, so they’re not as careful,” Dr. Baughman said. “That in it of itself is kind of paradoxical, even though you would expect the headgear for soccer to reduce concussions.”

“In terms of the scientific research, the clinical research on wearing protective headgear in soccer, there’s no evidence to suggest that it guards against concussions,” Dr. Baughman said. “It’s kind of like football. You can get the most high-tech football helmet, and you still might have a concussion because what helmets are designed to do is not to prevent concussions but to prevent skull fractures. There is no concussion-proof helmet.”

St. George’s makes protective headgear optional for soccer players. Mr. Tony Whicker, head coach for both varsity boys and girls soccer, believes that soccer is not at a point of requiring headgear yet, though he supports requiring it for women’s lacrosse.

Mr. David Wolff, head coach of both varsity boys and girls soccer at Houston High School, believes soccer should already be taking action, which is why he requires his defenders to wear headgear.

“About 2007, I got my first player who had chronic concussions,” Mr. Wolff said. “One of the things I noticed about that was that she didn’t have as much tentativeness about her play as she did when she wasn’t wearing [protective headgear]. I really believe that being tentative is one of the things that’s going to be a contributing factor to concussions. Having whatever apparatus it is hit you is a lot different than you actually being the one who initiates the contact.”

Dr. Baughman is less hopeful about players being able to avoid concussions.

“I think there is not going to be any definitive prevention of concussions. Anything that you do where you’re going to expose your head, there’s a possibility that you’re going to have a concussion,” Dr. Baughman said. “Understanding and knowing how to identify when someone is having a concussion is even more important than the prevention side of things. And we’re getting better at that. The other part of it is there’s been rule changes. I think if anything has helped prevent concussions, it’s changing the rules around.”

Football, specifically the NFL, has made rule changes in an attempt to prevent concussions, including moving up the kick-off line, preventing “defenseless” players from helmet-first hits to their heads and necks and penalizing players that tackle opponents with the top of their head.

The new rules may have been made in response to the declining number of kids playing youth football. According to a USA Football study, participation in youth football dropped from 3 million in 2010 to 2.8 million in 2011. This decline occurred shortly after the first congressional hearings which revealed that the NFL was covering up the connection between concussions and mental illness in 2009.

Pop Warner, which is the largest youth football project in the United States, had a 9.5 percent decrease in participation from 2010-2012, largely due to concerns about concussions.

Grisham thinks the problem is only going to get worse.

“I think you’re about to see tackle football be completely gone until, the very earliest, middle school, if not high school,” Grisham said. “From my research, from my personal experience, little children should not be playing tackle football, at all.”

Dr. Baughman said that families shouldn’t be too hasty in rejecting sports based on concussion risk, however.

“I don’t think the concussion issue is such that the potential dangers of concussions outweigh the positive aspects of being involved in a sport,” Dr. Baughman said.

But based off of Rodgers’ story, some might disagree.

According to a study published online in the journal Pediatrics, it normally takes less than three months for people to recover from concussions, but it’s been over a year and Rodgers still suffers from memory loss, headaches, dizziness, trouble focusing and lack of balance. She also has symptoms of dyslexia and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, which she did not have prior to the concussion.

“No doctor has a reason why,” Rodgers said. “My biggest effect is memory loss, so I can be having a conversation with someone and in the middle of the conversation I’ll have no idea what you were talking about five seconds ago,” Rodgers said. “Or, I’ll be writing down my notes, and then I’ll come to class the next day and I’ll see the notes I have written, but I have no recollection of writing notes. There’s a lot of dizziness, and I faint a lot.”

Before her concussion, Rodgers thought they were a minor injury. “I didn’t really know anything [about them]. It never really crossed my mind before,” Rodgers said. “I figured you’re out for a week and that was it.”

But both Rodgers and Spadafora have changed their minds on the seriousness of concussions because of the long term-effects of theirs.

“Doctors will tell you the risk, trainers will tell you the risk. Keep that in consideration,” Spadafora said. “When you have family, do you want to be able to remember to pick up your kids? This year I was in the hospital once because of my head, and I think that really changed my perspective on everything.”