With great power comes great responsibility

A new generation of students is redefining popularity

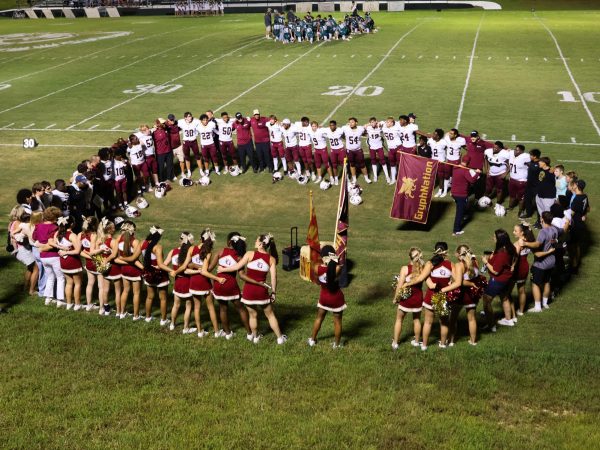

Photo: Elle Vaughn

“Having friends”

“Being recognized”

“How well-known you are”

“Having a high social status”

“Being kind and funny”

“Having lots of people like you”

“A social construct”

“Non-existent”

“Insecurity”

“Unfortunate”

“A worthless title that means nothing”

When asked to define popularity, St. George’s students have a lot of answers.

“I feel like the word popularity has such a bad meaning with it,” senior Megan Umansky said. “When people talk about it, it’s usually in a negative way.”

Junior Winston Margaritis has a different view.

“It can be viewed in a negative light,” junior Winston Margaritis said, “but I think it’s a good thing to be popular because that means that you have a lot of friends, and you’re very accepting of a lot of people.”

Talking about popularity is difficult since we can’t agree on a definition, but it turns out that’s not our fault. Scientists have found two different definitions of popularity, although both are united by a type of “superpower.”

In 2015, a study published by an Australian paper found that popular kids have one common factor: they all possess something referred to as an “advanced theory of mind,” which gives popular people the ability to better understand other people’s mental states and influence their behavior. The study suggests that there are two kinds of popularity: “sociometric popularity” and “perceived popularity.”

Sociometrically-popular people use their skill to be empathetic and better communicate with others. However, people with perceived popularity use their advanced theory of mind to manipulate their peers and gain higher social status. In other words, popular kids are superheroes who can use their “power” for either good or evil.

In order to better understand what popularity is, the Lodge sent a survey to both the middle and upper school asking about how much certain characteristics contributed to someone’s popularity. What we found was a profoundly negative attitude towards perceived popularity and a growing recognition of sociometric popularity as desirable. While almost 80 percent of students believed that looks did affect popularity, over 50 percent said they shouldn’t. On the other hand, 60 percent of students said how you treat others doesn’t affect popularity, but over 95 percent said it should.

In addition to these characters, many students recognized the archetype of the stereotypical “mean girl” and responded negatively towards that idea.

“Kids that are partying a lot or doing whatever people are thinking is cool at that moment, they can sometimes be deemed the popular kids,” Ms. Amy Michalak, director of counseling and guidance for middle school, said.

However, high school isn’t the only place where people see this kind of popularity. Pop culture, including social media, TV shows and movies, also seem to perpetuate “perceived popularity.”

The 2004 film “Mean Girls” is one of the best examples of media depicting “perceived popularity.” The antagonist of the movie, Regina George, is the epitome of negative popularity, since, throughout the movie, she shows that she’s willing to do anything to improve her, already high social status including destroying the reputations of others, in the process.

“There is a reality to those perceptions,” Ms. Michalak said. “I think that when you watch a movie like ‘Mean Girls’ that’s showing the extreme. It’s funny because everybody can feel little pieces of that, so we laugh. It’s nice to see that being made fun of, in a way. It’s comforting to everybody who’s been slighted at some point, so we enjoy that for entertainment.”

Media portrayals of perceived popularity can spread into real life, giving all popularity a bad name.

“Everyone automatically assumes that you’re rude, you’re arrogant. Generally speaking, if you think of a popular person, they’re not smart, and they just come across seeming that they’re better than everyone,” sophomore Caroline McDowell said. “People who consider me popular have judged me based on what kind of person they think I am, and they actually don’t know who I am.”

Freshman Reagan Burford agrees.

“The disadvantages of being popular is people around the school who aren’t considered popular look at you a different way, thinking that you’re bad just because you’re known and you’re nice,” Burford said.

Several students responded that they felt St. George’s didn’t have the same problems with perceived popularity that are depicted in the media.

“I don’t think that we have that situation, the typical bully situation [where] popular people would pick on the nerds or the unathletic people. We really do not struggle with that. Everybody is nice to each other, and everybody really cares about each other,” Burford said. “We don’t really have any people who are mean about it, but that definitely happens at other schools.”

Some think it’s completely unfair to think of being popular as being a “mean girl.” In interviews, many students felt that “sociometric popularity” is more prevalent for today’s generation, meaning that the typical understanding of popular is going out of style. Popular people are no longer the dumb jocks or “mean girls,” but rather people who strive to be great leaders and are well-liked among their peers.

“You’ve got the popular kids that are all really smart. You have the popular kids that are

the athletic ones and the artistic ones, so people are popular in their own sort of way,” Prefect of Student Life Kneeland Gammill said. “Going back to the stereotypical popular kid, I definitely think that’s something that’s outdated, especially in the St. George’s community. I don’t see kids in that light here.”

Is “perceived popularity” a fading trend like bell-bottoms and flip phones? Only time will tell.