Challenging the routine

Dr. Jieyong Qian shares her re-education story

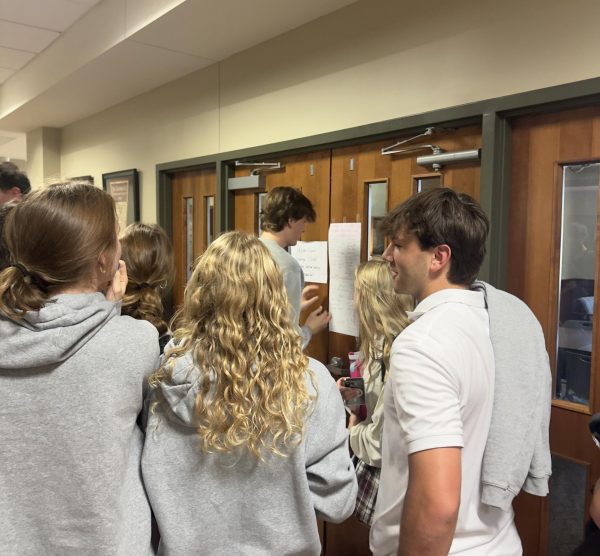

Photo: Alice Crenshaw

Dr. Jieyong Qian speaks to a group of students in the Agape chapel about her experience with re-education. At the age of sixteen, Dr. Qian was separated from her family and forced into labor with herders.

By sophomore year, students generally know what to expect when reading a novel in class: read, annotate, discuss and then make a presentation or write a paper. But this routine is being challenged by Mrs. Ricketson’s 10th grade English classes, who had the opportunity to learn about the cultural context of their novel “Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress” firsthand from Dr. Jieyong Qian.

“Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress” opens in 1971 during the Cultural Revolution, a time period Dr. Qian remembers well. During this period, Communist Party Chairman Mao ZeDong decided to reinforce his party’s ideals by sending intellectuals and members of the upper and middle classes to villages and rural areas to be re-educated by means of menial labor.

Students had the opportunity to hear about this directly from Dr. Qian, who was sent to a village in Inner Mongolia at the age of 16 as part of the reeducation process.

“My older brother left for the countryside in 1967, thinking that by going himself he would save me and prevent me from going,” Dr. Qian said. “He told my mother ‘keep her with you. Let me go.’ So he went, but that didn’t happen. The next year I went, and three years later my [younger] brother had to go. No one avoided that.”

In the countryside, Dr. Qian was introduced to an entirely new way of working, eating and living. Like the characters in “Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress,” Dr. Qian questioned the value of reeducation and the effect it had on her generation.

“Yes, we learned a lot from the herds people. We learned how to survive hardship, and we learned how to find happiness from small, simple things,” Dr. Qian said. “But is it worth it to basically take the best five years of your life to go to the countryside like that? I think not. But unfortunately that was my generation’s experience.”

Many students were intrigued to hear about her real life reeducation experience.

“The most interesting thing that she said was how after all of the things she learned in inner Mongolia, it still wasn’t worth it and how she lost a part of her life that she could have spent in other ways,” sophomore Silas Rhodes said. “What I enjoy about this type of learning is the firsthand experience from the speaker. It allows me to have a personal connection to their stories.”