Dyslexic Goldilocks

Finding the right definition of dyslexia

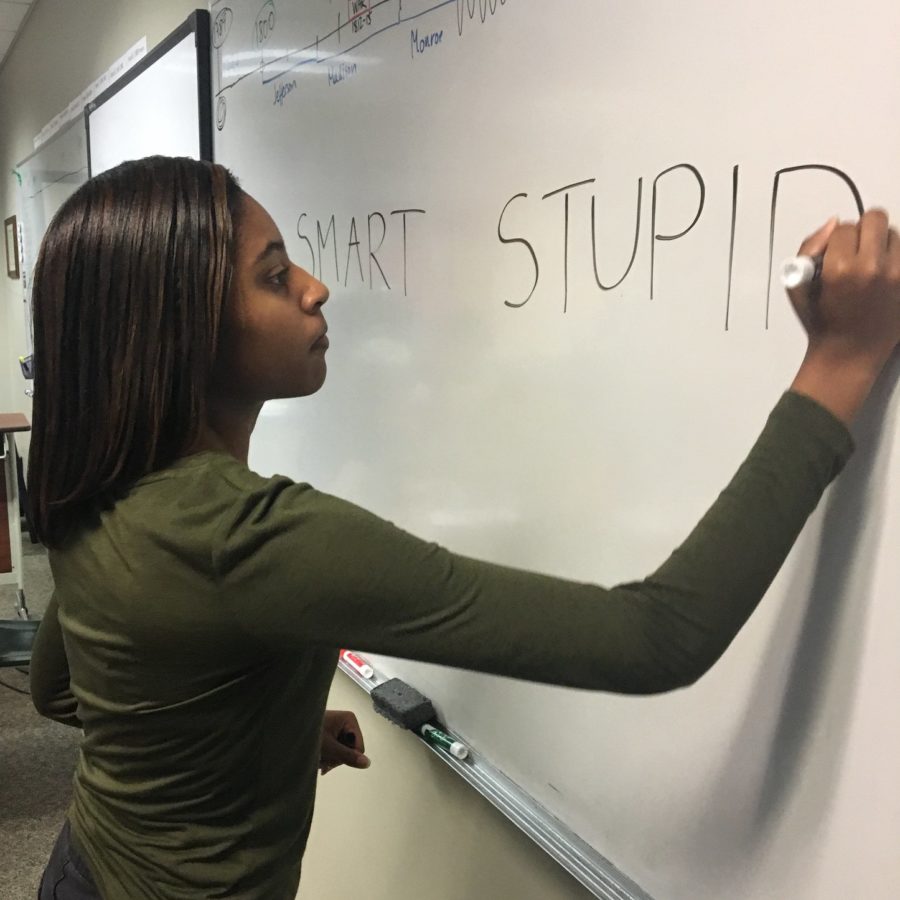

Photo: Annika Conlee

Junior Lauren Purdy writes smart or stupid on a white board. The debate over the definition of dyslexia has evolved over time and should eventually reach a middle ground.

At three, I mumbled but never spoke. In second grade, unable to do daily timed math work sheets, I would cheat. That same year, embarrassed by my difficulty with writing, I would fiercely cover my paper in class, so no one would see my inability to spell basic words or even copy sentences from the board.

Speech therapy as a toddler cured my first symptom. Luckily, my second grade teacher noticed the signs and and suggested I get tested for dyslexia. From then on until seventh grade, I received extensive tutoring from a dyslexic specialist after school. My parents sacrificed an incredible amount of money, and I dedicated so much of my life to overcome the challenges of this diagnosis.

Now, it’s five years later, and this same diagnosis has been cast in a much different light.

Rather than referring to dyslexia as a learning disability, it has been re-labeled as a learning difference, with some even going as far as to call it a gift.

Blake Charlton, a New York Times journalist, attended an Emily Hall Tremaine Foundations Conference on dyslexia and reported that the conference declared that “dyslexia is not a disability” and that the successful dyslexics attending achieved their success “not despite their dyslexia but because of it.”

“Dyslexia is not a diagnosis at all,” Mr. Charlton wrote. “Labeling it as such pathologizes a normal variation in human intelligence.”

The definition of dyslexia contradicts this statement though.

According to the American Ministry of Education, dyslexia is “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations.”

According to New Zealand’s Ministry of Education, of dyslexic children whose fail to be diagnosed and as a result remain poor readers in third grade, 74 percent will remain poor readers for the rest of their life.

Reading is a fundamental skill that is both vital to education and productive involvement in society. Anything that can seriously challenge that skill is not a gift. It is not a different type of smart but rather an obstacle to overcome.

Social stigmas tend to follow dyslexia. Many uneducated individuals simply believe dyslexia is another word for stupid. While rare, comments like these feed a deep-set fear. “Do others secretly think I’m stupid? How can I prove that I’m not? Do you need my ACT score as proof?”

I am proud that I have dyslexia. I am proud that I conquered it. But dyslexia did not make me smart or stupid. It made me a hard worker. It made me grateful for the help I received.

The idea that dyslexia is a gift is not the cultural norm, and it needs to be prevented from becoming it. Replacing an incredibly negative viewpoint with an overly positive one is not the answer though. As a culture, we should strive to properly define dyslexia where it truly lies, somewhere in the middle.