Together We Serve

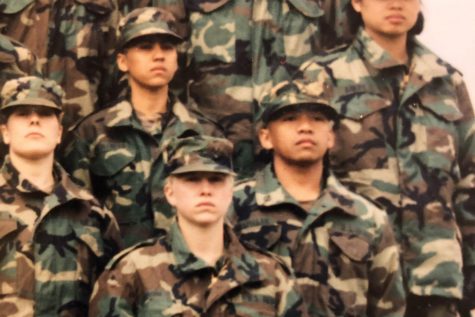

A tribute to our faculty members who served

“I joined the military because it felt like it was the right thing to do,” Middle School IPS teacher Mr. Mike Smothers said. “There wasn’t a war on. It wasn’t this heroic mission thing. It was more that, I wanted to contribute. I wanted to help in some way.”

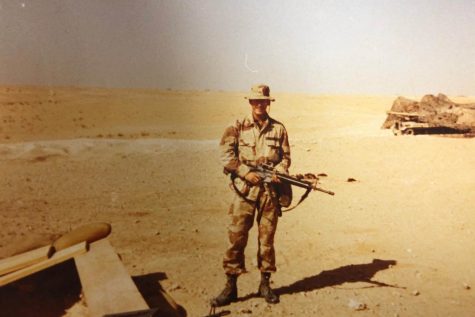

Mr. Smothers was about twenty years old when he enlisted into the military, and he was in for a total of eight years working as a combat engineer in the army. He did active duty for three years, where he lived in Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm and eventually went into Iraq to fight the Iraqis. The other five years, he was reserves and national guard only training one weekend a month and two weeks in a summer.

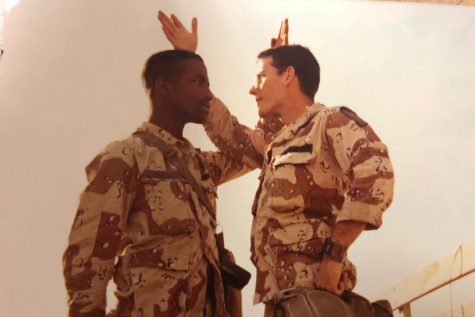

“Joining the army, that was the first time I was in an environment where I never ran across anybody who knew who I was. No one knew who my dad was, so I was being judged solely on my own characteristics, my own work ethic, my own sense of honor, so that gave me the confidence,” Mr. Smothers said. “When I came out of army, I was a much more confident individual. I was much more self assured that I could handle things.”

In the military, Mr. Smothers worked with tanks, and wherever the tanks went he went. His job was to protect the tanks and he did this by either shooting enemy tanks from underneath or opening up berms so that his tanks could go through them. He blowed up the enemies tanks and protected his own. Because of this, he was deployed to Saudi Arabia to help in case tanks malfunctioned.

“Honestly 90% of your time in service is waiting for something to happen or, just as you’re waiting for things to happen, having to do the drudgery of doing vehicle maintenance, weapons maintenance, cleaning equipment, waiting to clean equipment,” said Mr. Smothers.

Surrounded by Saudi Arabian desert, Mr. Smothers and his platoon had to find ways to help themselves, such as playing jokes on each other, playing cards or naming bugs they saw. They had to look for the positives.

“I remember we’d be on guard duty. If it was new moon, so a moonless night, it would be so dark out there,” Mr. Smother said. “Horizon to horizon, you would just see stars all over the place, but then if you looked at the ground, totally black. You couldn’t find your way around because it was totally dark, but the sky was so amazing. I’ve never seen a sky like you see in a desert. It’s just beautiful.”

After spending months in Saudi Arabia waiting for the war in Iraq to begin, his platoon was finally deployed there when they needed to prevent Saudi Arabia from being an invaded by Iraq. His platoon’s mission was to distract the enemies while other soldiers attacked from behind them. They were successful, but it wasn’t until after it was completed that he realized how much danger he had put himself into.

“I remember very clearly SergeantNelson, our platoon sergeant, coming in. I had just gotten off of guard duty about an hour before, and I remember Sergeant Nelson coming around to all the vehicles in our platoon saying, ‘Alrighty, get up. Get your kit together. Get ready to roll. Be ready to roll in twenty minutes’,” Mr. Smothers said. “And I remember seeing some patriot missiles getting shot over head, which generally we took to mean that there were scuds that had been launched. Scuds were the enemy missiles.”

It was a start of a war. This is what he had trained for.

“I remember seeing missiles go over head. Guys put on their gas masks. We’d basically been given a signal, ‘Hey, be prepared for a gas attack or something.’ And then vehicles just started moving out. This was probably three o’clock in the morning,” Mr. Smothers said. “As dawn approached, I remember looking left and right, and as far as you could see, there were vehicles moving, going up to the border.”

Although he could have died, he never thought twice about what he was doing during the mission because he knew exactly what his job was and how to handle it.

“One of the little bits of wisdom that our training sergeant used a lot was that the more you sweat in peace, the less you’ll bleed in war,” Mr. Smothers said. “Meaning that we want your training to be so challenging that you’re just going to know it without having to think.”

Middle school US history teacher Ms. Traci Erlandson joined the military because she wanted the experience of her grandfathers and her father. She served for seven years as a reservist and worked as a combat medical and psychiatric specialist. However, before any of that, she had to leave and go to San Antonio for a year for basic training.

“It’s lonely. Even though you’re around a bunch of people, you don’t know them. It takes a while to get to know them, so I was really lonely,” Ms. Erlandson said. “That’s when Seinfeld was a big show so on Thursday nights — Friends and Seinfeld, that’s what we did. I missed going over to my friend Dave’s at CBU and just watching Friends and Seinfeld, so they wrote me a letter and then did little cut-outs of the Seinfeld characters, and it was a pop up letter. It was so cute. I depended on communication from my friends and family.”

Even while doing basic training, Ms. Erlandson had to sacrifice and felt lonely and disconnected with the people and friends she left behind. For two months, she was not allowed any newspapers or radio. She had some personal time to call home, but she was mostly cut off. When she came back, it felt different.

“I felt like I had changed. I was so worried about everybody changing and forgetting me, time going by [or] not forgetting me, but not having shared memories,” Ms. Erlandson said. “But, when I came back, everything seemed completely the same, but I felt different. I knew I had changed.”

She had made connections with people from all over the world in the military, and so she felt as though she had grown up.

“I had a different worldview at that point just because of my experience, and when you’re in the military I guess, you’re just surrounded by people from all over the country,” Ms. Erlandson said. “Suddenly you have a shared experience with these people, but then you come home and you’re away from that, and unless you’ve done it, you don’t get it.”

In training with the military, Ms. Erlandson remembered learning the importance of trusting the other people she was training with, as they all relied on each other. If one person talked during lights out, everybody would have to run. She even remembers training with grenades hoping no one in her group set them off. She had to trust them with her life.

“I remember when we threw live grenades. They gave us two live grenades, and before you go out to throw your grenades, it’s a platoon of us lined up in this cinder block room,” Ms. Erlandson said. “Everybody up and down the line, you’re looking at these people that you still don’t know very well, and you’re like, ‘God, I hope nobody loses it right now because all they have to do is pull the pin.’ I remember that vividly. And we had some loose cannons. We had some guys where you were like, ‘They could kill us. These people could kill us right now.’”

Ms. Erlandson even spent her 21st birthday at the training camp. While other people have a party, Ms. Erlandson had to do 21 push ups while other people in her platoon sang her happy birthday.

“My dad and my step mom sent me 21 roses, and I had KP, so I had kitchen patrol It’s the worst. You talk about actually peeling potatoes. It’s not fun,” Ms. Erlandson said. “So anyways, they were like, ‘Erlandson, get out here.’ And I’m like, ‘What did I do? I’m in so much trouble.’ And so, they’re like. ‘Okay, I hear it’s your birthday. 21!’ And they got everybody in mess hall to sing happy birthday, and I’m just sitting there doing pushups like, ‘Oh, this sucks.’”

Sometimes, Ms. Erlandson wishes she had stayed in the military and become active duty and traveled places to help other countries, but she decided to become a teacher and thinks she was more suited to teach her students.

“I do take pride in the fact that I served and I can say I served,” Ms. Erlandson said.

Technology support specialist Mr. Kevin Cranford joined the military when he was 19 years old and stayed in for four years. He was an aircraft mechanic that worked on life support equipment on f14s.

“As a kid, I was always obsessed with fighter jets,” Mr. Cranford said. “I knew I was never going to be able to fly, so I thought being a mechanic would be fun as well.”

He went to many different countries around the world working on airplanes, but the most memorable part of his experience happened in Jordan. He went to Jordan because Sandhu Sen’s daughter and son-in-law left Iraq and entered Iraq, and troops came to help defend the border. He saw a life-changing sight when he got there.

“What we saw were a lot of Kurdish refugees going across the border and I saw their conditions from what they were experiencing in Iraq as they came into Jordan seeking refuge. It was an eye opener,” Mr. Cranford said. “It’s just stuff you don’t normally see in this country. Even the poorest people you see in our country aren’t living like that, so it was an eye-opener to what was going on in the rest of the world.”

He talks about how much he grew up after coming out of the military and seeing those experiences. It changed his worldview, and he encourages other people to also join and see what is happening outside of the world.

“A lot of times I was still a person, even though I was in the military saying how I don’t know if we should be involved with other countries,” Mr. Cranford said. “When you see that, you go ‘yea, someone needs to help them.’ We can’t just sit back and go ‘oh, it’s not our country. We shouldn’t worry about it.’ because somebody needs to help those people.”

Mr. Cranford sacrificed significant parts of his life to join the military even when it wasn’t a time of a world war. He left his family and could only talk to them for a little bit every once in a while. He served for four years, and sometimes could only contact his family through a satellite phone which made phone calls that were ten minutes feel like five minutes because of how long it took to hear each other. However, no matter how long you join the military or what you do, sacrifices are made.

“Anyone in the military would willingly lay down their life,” Mr. Cranford said. “Not everyone is asked to do that, and that’s a great thing that not everyone is asked to do that.”

***

We give thanks and respect to our veterans because they risk their life regularly in service to those back home.

“Care about the soldiers, care about the military, the service members who made a choice literally to sacrifice their live by serving because they’re away from your families,” Ms. Erlandson said, “and they don’t know what’s going to be asked of them.”

While we have respect for service members, also know what all goes in to the larger military service. There are so many parts that make the service that fight for our country, not just soldiers.

“When people hear military, they start thinking Seals, Rangers, Green Berets. Well no, there are guys who are cooks. There were folks who were medics. There were people who were mechanics,” Mr. Smothers said. “There’s a lot that goes into that, and even if it’s not kind of the glorious jobs, there’s still value, and there’s still worth to it, and it’s all work jobs because it contributes to something larger than the individual, and that’s a good thing for people to dedicate themselves to something bigger than themselves.”

People often think of military in a mythic way and that people are always in war with each other all the time, but it’s not always like that. Sometimes soldiers wait for a war to happen.

“It can be all too easy to hold up veterans on a pedestal and say that this is the way veterans are, and all veterans are different,” Mr. Smothers said. “The experiences of veterans are all going to be different because everybody comes to it from a different place.”

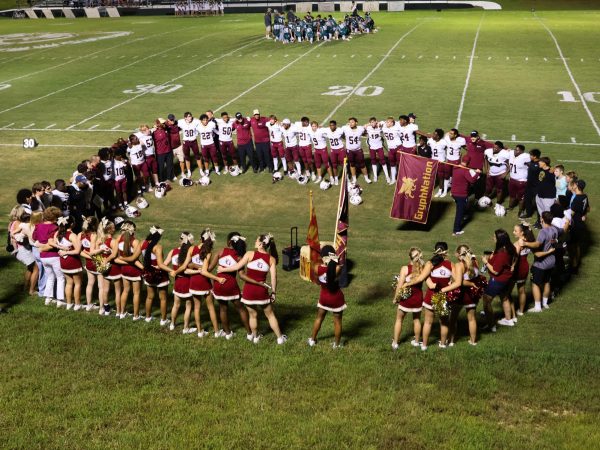

It’s all the people on the force who are helping this country. It isn’t just the soldier. It isn’t just the mechanics. It isn’t just the aircraft mechanics or psychiatric specialists or engineers. It is all the people in the military coming together. They protect the country together. As we move away from Veterans Day, it helps to remember that people like Ms. Erlandson, Mr. Cranford and Mr. Smothers who carry their service with them every day.

“The military isn’t noble and it’s not mythical. It’s people. The sum total of our cultural value is determined by who the ordinary people are. If ordinary people are willing to sacrifice and commit to something other than themselves, I think that says a lot about our country,” Mr. Smothers said. “That’s what I would want people to look at veterans as, kind of a model of we could do something. We could contribute. I’m just one, but I could be one who does something.”