Ruling the school

Administration should have a say in elected student leadership

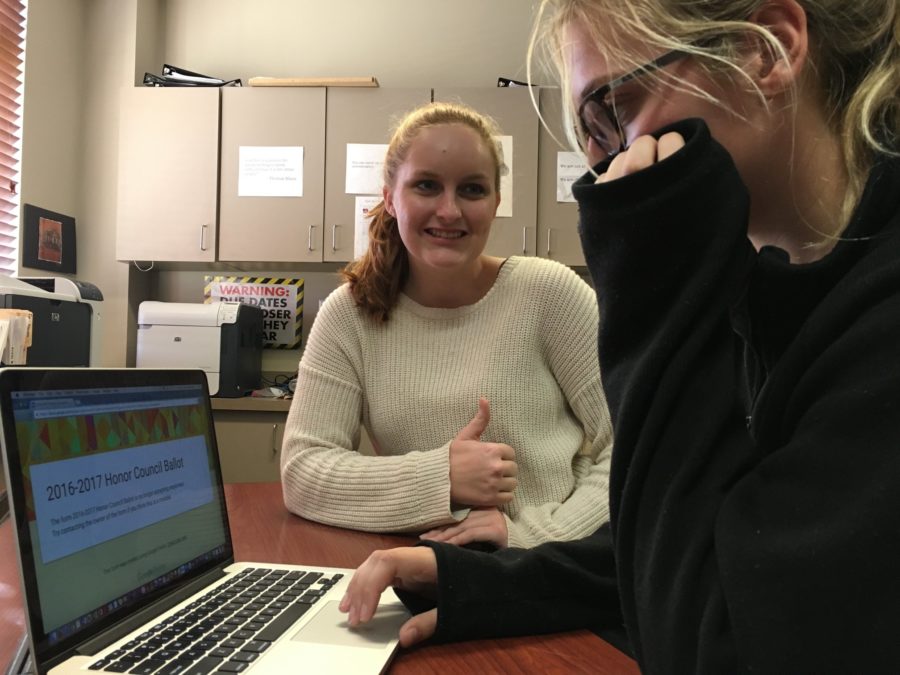

Photo: Caroline Zummach

In this posed photo, junior Katelyn Grisham votes for Honor Council while her friend, junior Carolyn Lane, watches closely. Lane believes that administration should have a say in student elections.

The 2016 presidential election was considered “a disappointing franchise entry” according to Forbes. One candidate was called a liar while the other was deemed a racist, and many believed neither should have been able to run for office.

While candidates for student elections at St. George’s will hopefully never be as notorious as the last presidential one, we lack a system to prevent the election of an official that does not represent our student body.

According to Allie Bice, a reporter for the State Press – Arizona State University’s student newspaper – elections for student leadership are a game of who knows whom.

“ASU student government elections are popularity contests,” Bice wrote. “They’re all about who knows whom, and the executive ticket with the biggest social circle typically wins.”

Popularity has been defined in many ways over the years, but no matter what definition is created, popularity’s influence on high school interactions always prevail. Thirteen-year-old Daniel Spilo, who was quoted in the New York Time’s article “Relationships; Popularity: Fears of an Adolescent” about the role popularity plays in schools, provides one interpretation.

”Popularity is similar to population. It means having a lot of friends,” Spilo said. ”It doesn’t have to be for the right reasons and most of the time it is not.”

Popular individuals are often influential in student elections: they know the most people and have a familiarity that makes listening to or voting for them easier.

A major problem with voting by familiarity is that you are voting for a person based on who they are rather than what they hope to accomplish. Just because someone is a good person does not mean they are a great leader.

With the creation of a new student government election process this past school year, I believed St. George’s was creating requirements to run for student office. I myself completed the process, which included answering six questions and conducting an interview with current members of Student Government.

I was under the impression that the process would give students not considered to be a part of the “in crowd” a more equal chance at being elected and remove candidates from the ballot that were unfit to hold office due to Honor Code infractions, a lack of ideas or a lack of desire to actually hold the position they were running for.

However, candidates were not weeded out of the process. Maybe we were all qualified, but what if we weren’t?

To solve the issue of popularity in student elections, the administration simply needs to adjust the system already set in place. If an interviewee has been in front of the honor council within the past year or lacks credible plans or ideas to improve student life in the future, the administration should have the power to remove their name from the election ballot.

The administration also deserves the right to remove an individual from an elected student leadership position, such as student government, honor council or prefect, should they be called in front of the honor council or get in trouble with the law during their term.

If presidential candidates are required to fulfill specific requirements, student leaders must conform to certain standards of criteria as well.

Despite what some may believe, though, I am not bitter. I have never considered myself a part of the “in crowd,” and as a result, I entered the Student Government election with the assumption that I was going to lose. That is something no student should ever believe.

As country who just finished an election with “the worst nominees in 40 years” according to The Huffington Post, we must learn, even at the high school level, to vote for agendas and plans, not just for personalities.