Where Do You Draw the Line?

Once redlined neighborhoods are continuing to face many forms of discrimination

Photo: Madeline Sisk

This illustration depicts a crack or divide between two contrasting backgrounds. People who live in once redlined neighborhoods are continuing to feel a separation from society and being able to obtain equal opportunities.

I live in Memphis Tenn, and as I drive downtown, I pass by streets that have freshly cut lawns and newly painted houses, but the next street over could be vacant with trash covering the lawns and homes with broken windows. I find myself asking, why is the poverty of my hometown so bad, and how can we as a community help these neighborhoods that are suffering today?

The answer isn’t black and white, but one reason can be traced back to redlining – a policy originally implemented 90 years ago that refused insurance, loans or other various services to someone who lives in an area that has in some way been deemed a ‘poor financial risk.’ In the 1930s, government surveyors gave neighborhoods in 239 cities in the United States a ‘grade’ based on a range of options between ‘best’ and ‘hazardous.’ The neighborhoods that were outlined with red lines were deemed ‘hazardous’ and were denied services both directly as well as with the selective raising of prices. While redlining was banned by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the implications are still felt across the nation and in my hometown.

In Memphis, the majority of victims were black residents whose neighborhoods were labeled mostly because of their racial and ethnic demographics. Initially, redlining incited white flight, where many middle class white families moved out of redlined neighborhoods into more financially stable ones and has laid the groundwork for other future continued discrimination that I believe can only be combatted through actively being an antiracist.

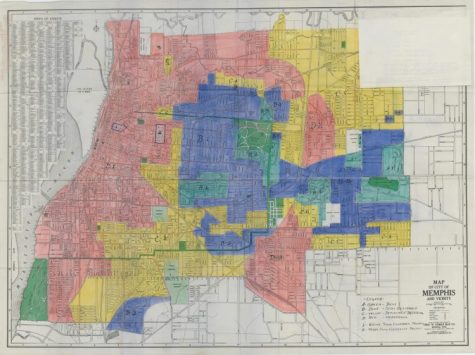

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation drew this map of the city of Memphis in the 1930s. North Memphis, South Memphis, Downtown and parts of Orange Mound and Binghampton are all outlined in red.

South Memphis, North Memphis, Downtown and parts of Orange Mound and Binghampton were all outlined in red, and 90 years later, these neighborhoods are still seen as the most underprivileged areas in the city of Memphis. According to the 2019 Update of the Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet, Memphis has a poverty rate of 27.8%, and the black residents have been hit the hardest. The poverty rate for the non-Hispanic black population is 33.8%, while the poverty rate for non-Hispanic white population is 11.8% in the city.

Negative effects of gentrification and banks refusing to give loans to neighborhoods that were once-redlined neighborhoods are still in use today and making it difficult for people to be able to move beyond the 1930s.

Despite redlining being outlawed in 1968, many businesses still practice discrimination to areas that were once redlined. According to High Ground News, black families face underwater mortgages and foreclosures at higher rates than white families. In 2012, Wells Fargo faced a lawsuit for $432.5 million for targeting minority neighborhoods in the city with predatory loans. In 2016, First Tennessee also faced a lawsuit for $1.5 million for refusing to give loans to qualified black and Latino residents. They also refused to put branches in minority neighborhoods in the cities of Nashville, Memphis, Knoxville and Chattanooga. How are families supposed to get out of poverty if the people who can help the most are refusing to provide service to help this community, our community?

According to a study conducted by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition in 2018, three out of four neighborhoods that were deemed “hazardous” in the 1930s are economically struggling even today.

This has not only affected the Memphis community, but also the other 238 cities that faced redlining. Another way in which redlining is still haunting many residents of the United States is through gentrification. Gentrification is the process of renovating impoverished neighborhoods, houses, or districts and improving the district to conform to middle-class. The effects of this process are complex as it can bring benefits as well as consequences to the people living in the gentrified areas. Between 2000 and 2010, many places that were considered redlined neighborhoods underwent gentrification, which meant that the neighborhoods were seeing changes and improvement in the economy, home values, and educational systems. In gentrified places, there have been more interactions between black and white people; however, a greater inequality gap has been made between people coming into the now-gentrified neighborhoods and the people who had been living there before gentrification. Where do we draw the line? While there are benefits because gentrification is helping desegregation of some neighborhoods, many of the people who were living in the neighborhood before have been forced to move out because they cannot afford the rising prices. It was not their choice to live in redlined neighborhoods, but many racist policies have made it difficult for families to escape.

I recently heard Ibram X. Kendi speak at the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, and he talked about how to be an antiracist and the idea that people who support or are complacent with racist policies or discriminatory practices of businesses are racists. The only way to stop racism is to diminish racist policies, policies that hold back people’s potential, but also to stop companies and businesses from continuing to actively discriminate against the communities that need the most support. Kendi explained that colored people suffer more because of their skin, but when looking at a poor black or white neighborhood, they experience the same drug usage, drug selling, and other unfortunate experiences.

I propose that the United States stops gentrification and starts to bring about policies that help families get out of the impoverished neighborhoods they feel they are bound to. There is a difference between helping a community obtain more resources and helping a community to the point where they are no longer able to live there. Gentrification should not drive people away from the neighborhoods they lived in for their whole lives, but it should help them financially. There should be laws against banks refusing to support people who come from impoverished neighborhoods, and there should be a greater punishment for those that break the laws. Most of the banks I mentioned only lost a small percentage of what they make annually, and that almost seems like a slap on the wrist. How do we know that they will not continue to practice the same discrimination?

Policies that are helping the betterment of all people should be enforced because that is the American Dream. Any American citizen should have equal opportunities to achieve their aspirations in life according to the American Dream, but if laws are keeping some people chained to historical impoverishment and they cannot break out of that, then the laws need to be changed.