Stop and Listen

Hispanic and Latinx students struggle to be heard

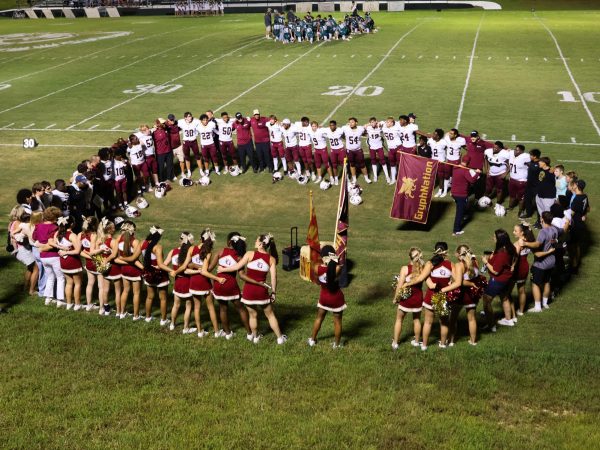

Photo: Callie Hollis

Eighth grader Jennifer Lopez poses looking through her locker. In the whirl of everyday school life, students can feel overlooked.

Memphis is a majority-minority city. According to the United States Census Bureau, 63.9% identify as Black or African American. However, just because there is such a large minority group, that doesn’t mean all people feel included or treated equally. People who identify as Hispanic and Latinx make up only 7% of Memphis’ population, and at St. George’s many of the Hispanic and Latinx students can only name a few others who go to the school.

Sophomore Iris Delahoussaye, whose mother is Puerto Rican, said that sometimes she feels underrepresented because of how small a minority group she belongs to at St. George’s.

“Besides myself, I can really only name three or four who are Latinx or Hispanic, and if I do see them, it’s just passing in the halls, so I feel like it’s not much representation there,” she said.

Junior Luis Lopez, who identifies as Hispanic of Guatemalan descent, has noticed the same thing.

Junior Luis Lopez stands on the stairs unacknowledged by the people walking past him. He can only name a few other students who are also Latinx or Hispanic at St. George’s.

“Every school year, my dad always asks the same question, ‘How many Hispanics are there?’ And I’m like ‘Dad, still two. Still two in my grade,’” Lopez said. “The most that I’ve seen in a grade is my sister’s grade, which has like five.”

Although some people may use Latinx or Hispanic interchangeably, these two words have different meanings. Hispanic refers to any person who speaks Spanish. It also refers to anyone who is from or has heritage from Spanish-speaking countries; however, Latinx, which is the non-binary form of Latino/a, refers to people from Latin America or those who have Latin American heritage.

According to Interim Head of School Timothy Gibson, St. George’s racial makeup is approximately 30% people of color. Though exact numbers were not readily available, anecdotal evidence suggests that students who identify as Latinx/Hispanic make up a small fraction of the overall school enrollment.

Race is not as transparent as some might some might assume, so it is not as easy to recognize students who identify as Hispanic or Latinx.

“Puerto Ricans and Hispanics and Latinxs in general come in all various looks. Some have lighter skin, some have darker skin, blue eyes, blond hair, brown eyes, black hair. We look like everything,” Delahoussaye said. “I feel like the only big reason why we haven’t been horribly targeted is just because we’re hard to spot, which I’m appreciative [for], but at the same time, I want to be noticed that I am Hispanic. I am biracial. But, at the same time, it’s kind of like a survival thing because if we can’t be spotted, we can’t get targeted, so it’s an odd trade off.”

The comparative invisibility of Latinx/Hispanic students can sometimes leave some people feeling left out of conversations about diversity and racism.

Though the controversial chapel talk at the beginning of the year specifically targeted African-Americans with racial stereotypes (for which the speaker later apologized), Lopez said he also felt demeaned.

“If you do that [referencing the chapel] to the biggest minority, what do you say about me?” Lopez said. “What do you say about my culture?”

In an interview with the Lodge last year, former upper school Spanish teacher Julián Guzmán, who now teaches at the University of Memphis, wondered whether Hispanic and Latinx students felt as fully included in the life of the school as he did.

“St. George’s is diverse. We have students and teachers from different cultures,” Mr. Guzmán said. “We have different languages that are represented in this school. We have different points of view about life in general, different religions, and that makes us a good community. But I always wonder how do [Hispanic/Latinx students] feel? Do they feel represented in the school?”

Mr. Guzmán encouraged all students of St. George’s to make sure that people of all backgrounds feel included and heard.

“You [the school as a whole] know that they are here,” Mr. Guzmán said, “but how many times do you stop yourself, and you talk to them and you connect with them and you understand how it is to be Indian, or Hispanic, or Asian, or African American?”

An Uphill Battle With Ignorance

Sometimes that lack of connection can lead to hurtful stereotypes, particularly when the subject of immigration comes up. On one occasion, eighth-grader Jennifer Lopez, who identifies as Guatemalan and is the younger sister of Luis Lopez, said she even hid in the bathroom to get out of a civics discussion about immigration.

“The book didn’t say, ‘Hispanics are all immigrants’, but it said, ‘the most’ [immigrants are Hispanic]. It said, ‘Of people who come to the United States, it’s mostly [from] Mexico.’ And so then whenever we talked about immigrants, everybody just stared at me,” Lopez said. “They don’t notice that immigrants are from all over. They’re not just Hispanics.”

Lopez said that some teachers and students have made assumptions about her being an immigrant because she is Guatemalan, and some students have made jokes about her crossing the border.

“I’m not that good at swimming. I mean, I can do it to save my life, but I’m not really good.” Lopez said. “They’re like, ‘Jennifer, you can’t swim, but you’re Hispanic. Didn’t you go through the water?’ I was like, ‘I didn’t. I was born here.’”

Her older brother Luis Lopez said he has not faced the same conversations, but he also understands that people can get touchy with the topic of immigration. He feels that people may assume the worst of immigrants before they know the full story.

“OK,” Lopez said. “My parents are immigrants. What’s the big deal?”

Lopez would like people to be more sensitive about the topic of immigration for those who have seen its effects.

“People in my family have been deported for being here illegally,” Lopez said. “Not people close to me, not my [immediate] family, but an uncle or cousin. They’ve been deported. It’s sad seeing the aftershock of that, and that’s what a lot of people don’t think about when they say, ‘Get rid of them. Don’t abolish ICE,’ stuff like that. They don’t see the damage that it leaves behind.”

Immigration is just one of many controversial topics Hispanic and Latinx students feel they have to contend with. Delahoussaye said she has encountered people that have a misconception that all Hispanics are Mexican, and all Mexicans are illegal immigrants.

Sophomore Iris Delahoussaye poses sitting on the stairs while being passed by fellow classmates. She said she thinks Hispanic and Latinx people can be easy to overlook.

“Sometimes I do get the whole prejudice behind being Hispanic of, ‘Oh, you’re Hispanic. Your family must be Mexican, and someone in your family must deal with drugs,’” Delahoussaye said. “A: I’m not Mexican. B: No one in my family deals with drugs. And then C: not all Mexicans deal drugs, so that’s just layering stereotypes on at once.”

In addition to stereotypes about Hispanics, Delahoussaye said that many people do not even know that Puerto Rico is a United States territory.

“I have heard, ‘Oh, your mom’s from the country of Puerto Rico,’” Delahoussaye said. “Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory, which means we’re technically still the United States. Meaning no, my mom’s not an immigrant. No, Puerto Rico is not a separate country, and no, I do not need a passport to get there because it’s part of the U.S.”

Junior Luis Higareda, who identifies as Latino, said he has encountered similar geographic confusion and that he did not like how many people have made assumptions that Mexico is the only Hispanic country in the world.

“Not only Mexicans speak Spanish,” Higareda said. “There’s other Spanish-speaking countries. I feel like people when they think of Spanish, they immediately think of Mexicans. Mexico is right under the United States, so it does kind of make sense why they would think that, but there’s other countries that are Spanish-speaking.”

Jennifer Lopez said she has also encountered people who misunderstand the scope of the Spanish language.

“We went to English mass, and this girl, she was like, ‘Can you speak Mexican for me?’ I was like, ‘Can you speak American for me?’” Lopez said. “And then she just looked at me. I was like, ‘You see what it feels like.’”

Owning an Identity

Lopez said that at first she did not stand up as much for herself and her culture, but she now has more confidence in doing so. At first, when she started introducing herself, she would always say that her parents are from Guatemala, but after a while, she grew confident in herself.

“‘My parents are from Guatemala. I’m Hispanic.’ That was the thing,” Lopez said, “but then I was like what’s the point of being embarrassed of it? Does it matter? So they’re like, ‘What are you?’ I’m like, ‘I’m Guatemalan.’ They’re like, ‘Oh, OK.’”

For Lopez, reconnecting to her culture came through music. When she forgot how to speak Spanish for a time, it was music that helped her learn even more than she knew before about the language.

“I don’t like to listen to music in English I guess,” Lopez said. “It’s just a thing because my mom and my dad, they listen to music only in Spanish. So I guess I just adopted that too, and I forgot how to speak Spanish for a long time, and music helped me build my Spanish up again.”

Although it took her awhile before she started to feel comfortable in her own skin, this helped Lopez see how unique she is. She knows that her confidence has grown in just a few years.

“I’ve gotten to the point where I was like you know what? If no one accepts me, who will? It hurts so bad,” Lopez said. “And then my mom, she was like, ‘Niña, no matter what happens, people won’t accept you. Every day is a battle for you, and just know you’re going to end up winning it.’”

Now, Lopez finds ways to push past the stereotypes.

“I wear big hoop earrings, and whenever I put them on, I don’t know, I just feel like nobody can stop me,” Lopez said.

Sixth-grader Melissa Villa, who identifies as Mexican, can relate to the struggle to stay strong and positive.

Villa’s role models are her big sisters and her mother. Their own triumphs through adversity has given her the courage to overcome the obstacles she may face.

“It’s just crazy to me how far people go in this school,” Villa said. “It’s so advanced, and it’s so stressful. [Her sisters have] had problems, and they still make it to the next grade and the next grade.”

Within the school community, Villa also has upperclassmen like Luis Lopez to look up to. As a leader in the MySpace Alliance club, whose mission is “to provide a safe space where students from all walks of life can share their experiences,” Lopez understands how hard it is to be a minority at school.

“I kind of feel like I’ve taken it upon myself to talk about diversity and be a leader for diversity,” Lopez said.

But he expressed some frustration at how long it has taken for the school to recognize the need for support for diverse students.

“It’s like now [the school is] starting to realize how important color is, how important having people of different genders and sexuality and socio-economic status and just everything that makes us different [is],” Lopez said. “Now [the school is] just starting to realize after I’ve been here for 14 years, after I had cousins who came here before me, after I have siblings now that [will] come here after me, after we’ve had graduates of color. It’s like it’s taken this long to realize how important diversity is in this school.”

Although there are many obstacles to being a minority, Lopez works hard to show off his Hispanic culture, and he wants others to be proud of their culture as well.

“Don’t let anyone tell you you’re not important because of your skin color. You’re beautiful the way you are,” Lopez said. “And I just think it’s important that you realize that being a minority isn’t something that should tear you down. It’s something you should be prideful in. It’s something you should be proud of doing, and it shouldn’t be the line between us. It should be the thing that helps us connect with each other.”