Colors You Can’t Ignore

Racism through the eyes of students

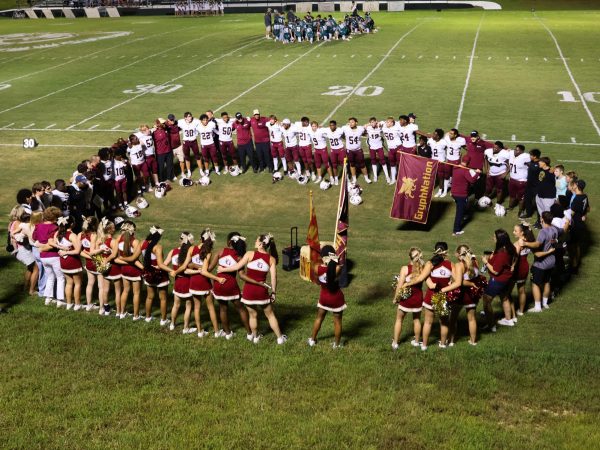

Photo: Laura Beard

“I chose my word because society over-sexualizes black women at a very young age, more than they do any other race.” – Kennadee Carlton

“When I see racism in the news and stuff, I think ‘oh, that’s terrible. It’s happening to so many people,’” junior Kennadee Carlton said. “I never really think about how in a few years, this could happen to me.”

Carlton is not alone in worrying about racism. A study by NBC news found that 64 percent of Americans believe that racism is still a problem. And a survey by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that 92 percent of African Americans said that discrimination against black people still exists today.

Racism cannot be defined without first defining race. According to the entry on the sociology of racism in the International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, race is “generally understood as a social category” in which groups are “distinguished by perceived common physical characteristics.” The entry defines racism as “‘an ideology of racial domination’ in which the presumed biological or cultural superiority of one or more racial groups is used to justify or prescribe the inferior treatment or social position(s) of other racial groups.”

At different points in history in the United States, racism has been directed against African Americans, Asian Americans, European Americans, Hispanic and Latino Americans, Jewish Americans, Middle Eastern and South Asian Americans and Native Americans.

African Americans in particular have been the targets of slavery, Jim Crow Laws and the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations.

While some of these experiences are in the past, African Americans still face racism today.

According to the NPR survey, 51 percent of all African Americans say that they have been called slurs because of their race, and 52 percent of all African Americans say they experience negative assumptions or offensive comments because of their race.

While some forms of racism are obvious, others are not as easily noticed. Sometimes subtle negative racial comments or assumptions are called microaggressions. These are verbal or nonverbal acts that communicate a feeling of hostility towards another person based on the group to which they belong. According to Simba Runyowa, writing in the Atlantic, microaggressions point out cultural differences and make minorities feel different. Comparing members of a race to their stereotype or simply touching someone’s hair because it is different are examples of microaggressions.

Senior Asia Gibson reports that even while walking around New York City, a city known for its diverse population, people touched her hair and asked her if she was from Africa because of her darker skin tone.

“When I go out of town and I go up north in straight towns where it’s only white people, there’s blatant racism,” Gibson said. “Someone will ask me or they’ll want to touch my hair, or they’ll be like ‘are you from Africa?’ and I’m like ‘does it look like I’m from Africa? Are you kidding me?’”

Even schools can be the sites of microaggressions. Gibson pointed to occasions when other students use the “n-word,” either casually in conversation or while singing along to music.

“They can listen to whatever type of music they want to listen to, but they don’t have to say the “n” word,” Gibson said. “That’s one of the things that really gets me is when people in my class say the “n” word, and then they think it’s okay because they say ‘well, [names another black student] hangs around us.’ That doesn’t give you the right to say that be cause you don’t know the meaning behind the word.”

Like Gibson, other students of color recalled instances where a white person called them the “n” word.

“I just think that they need to be educated on the words that they say before they say them,” Gibson said, “and they don’t understand that.”

Microaggressions can pose a significant problem for schools, which may struggle to address them. If peers at school point out ways in which minorities are different, they often feel alienated and may feel less welcome in school.

“[Racism is] a very real thing,” junior Jada Hines said. “Just because we’re more sheltered in a private school doesn’t make it invisible. It’s still there. It’s still going to be there for a long, long time. And it may affect some people more than others.”

When racial slurs or inappropriate jokes happen at St. George’s, Assistant Head for Educational Access Mr. Timothy Gibson (no relation to Asia Gibson) said the administration does its best to try to handle them even if the punishment is not always visible to other students. Mr. Gibson encourages students to seek out a trusted adult if they see situations like these.

“The first step is making sure that people know, because sometimes [students] assume that adults know, and we don’t always know,” Mr. Gibson said. “Then we take it from there and follow up and make contact with all involved parties to see what is the appropriate next step.”

But sometimes, students don’t feel that the school does all it can to combat racism. Carlton said that she would like for the school to take a more proactive stance against racism.

“I would like to see this school really acknowledge that racism is still alive, and it’s something that we as a younger generation should be taught to deal with and be taught to share with other people because some people in this school experience racism when we leave these doors [that] others don’t,” Carlton said. “I think that this school can help people to give them confidence in speaking up about how not to be afraid to talk about racism and really educate them on what racism is and how deeply it affects people, even the little things.”

Little things like jokes or offhand comments can have unintended effects on the people who hear them.

Senior Abby Walker, who is one-quarter Chinese, said she doesn’t know why people feel the need to point out her race to her.

“When people say you look really Asian today, I’ll think like ‘Oh, I need to look more white or something’, you know, or more American,” Walker said. “But, I mean, in the end I’m not going to change myself because people are saying this to me, I’m just going to…I don’t know. When I really think about it, looking Asian isn’t a bad thing. It shouldn’t be a bad thing. It’s who I am, so it’s disrespectful [to make comments about it].”

Sophomore Luis Lopez, who has Guatemalan heritage, said he has had similar experiences, especially when he is speaking Spanish with his family in public. He says sometimes he feels too “American” and too “Hispanic” depend ing on the people he is around.

“I felt like I had lost my sense of American-ness, like I wasn’t a true American because of how I looked,” Lopez said. “Even though I talked English, and that’s a big step, I wasn’t still the true American because I’m not a white person.”

Like Walker and Lopez, Carlton said she is sometimes the target of racial comments.

“I chose [my phrase] because within today’s society, being an African American female makes me question when I will be next to be a victim of a hateful crime.” – Asia Gibson

“You see any black person in a video or something, they’d be like ‘Oh, this reminds me of you’,” Carlton said. “We look nothing alike. We act nothing alike. We’re just both black, and that’s how I remind you of that person.”

But Carlton said she doesn’t let those comments bring her down.

“I think of myself as not less than, not superior, but equal to everybody else in this school, no matter what people say or do to make me think otherwise,” Carlton said. “It’s made me think that since you think I’m less than, I’m going to show you that I’m not be cause I’m going to show you that I don’t care what you think. That’s how I prove them wrong.”

Junior Malaisyah Vann said that racial comments make her more determined to just be herself.

“If me being me bothers you so much, then I obviously have something that you’re lacking,” Vann said. “I don’t know what it is, but it makes me feel like I’m gonna keep doing me and no matter what it is stay true to yourself.”

Of course, it’s not just white people who can can express discrimination. Within communities of color, colorism, or prejudice based on the relative darkness of a person’s skin color, can also cause discomfort.

Sophomore Ummu Bah said that she experienced colorism at St. George’s when some students of color said that she was “too white” to hang with black people.

“One day here in 6th grade, I remember I sat down with a group of girls and they were all like, ‘Sorry Ummu, no offense, but you can’t sit here.’ and I was like, ‘Well, what’s wrong?’ and they were like, ‘You’re not black enough,’” Bah said. “That was a question that came up there, or there’s a word that they called me in 6th grade, like an Oreo [black on the outside but white on the inside]. It really rubbed me the wrong way…so I can’t sit with you because I’m not black enough or I talked white, which I don’t even think you can talk a specific way. I remember I came home to my mom, and asked her, ‘Is there something wrong? Is there anything that I can control? Is it bad that I talk this way? Am I supposed to be acting a specific way?’”

Classrooms can pose different challenges. In history classes, African-American students particularly can feel that they are singled out when the topic of slavery comes up.

“I understand that we’re black, and we should be able to relate closer to this than our white counterparts, but I don’t feel like you should purposefully single us out because you aren’t doing that with a white kid,” senior Kaitlyn Bowman said. “If [we] want to talk about it, we should raise our hand like we do with any other subject. So don’t ask like if we can relate or if we have any to add or anything like that on a topic. Don’t assume that I should answer because I am black.”

Asia Gibson agreed.

“It’s okay because we have to talk about it. In every history class we have to talk about slavery, which is understandable because you need to know that content, but if you’re the only black student in the class, the teachers always come to you and are like ‘is that right?’” Gibson said. “And it’s like, why do you have to single me out because I’m black, and you think I would know the experience, but I don’t know the experience my ancestors had.”

Dr. Marianne Leung, who teaches U.S. history and chairs the history department, knows that students aren’t always treated equally in the classroom.

“Research shows that teachers do treat different ethnic groups different in the classroom,” Dr. Leung said. “There’s plenty of research to back that up that we have different expectations and so on, and we try very hard here to not. We are aware of it, and we have trained on it, and we are trying very hard to not do that, so if students understand that our intentions are 100 percent good, then give us some slack too be cause we’re trying.”

Dr. Leung said she does not feel like she singles any students out, but knows that students may perceive things differently.

“I know there are many times where students are assuming that I’m saying one thing when I’m not because that’s what they expect me to say because of their assumption of who I am, and I have probably done the same thing,” Dr. Leung said. “But that’s the nature of being in a community where you have many differences. You are going to have many misunderstandings, and the beauty of that is that you can actually learn from that.”

Ms. Indigo Bailey, who teaches African American history in the upper school, has experienced the same situations Gibson and Bowman explained. Ms. Bailey said because of her family’s background in the civil rights movement, during high school she would be asked to take her teachers on field trips to places like her family court house. They would ask her during class what she thought about subjects that involved her heritage.

“I guess it troubled me to have all that pressure, but now I take it as: it made me this right here,” Ms. Bailey said. “It makes you question something you shouldn’t have to question as a child when you get singled out, but kids should also feel empowered by their backgrounds and not feel troubled by the fact that people don’t know their experiences until they ask you. Sometimes it’s just a genuine curiosity, and we shouldn’t be offended by that. It shouldn’t be so taboo to ask people about their backgrounds or talk about their experiences.”

Ms. Bailey understands that sometimes talking about race or heritage during class could be hard because teachers may find them selves singling students out by accident. Her advice is to not use student experiences as examples during a history lesson.

“If I even talk about something that deep or that sensitive that could affect somebody’s heritage or how they’ve been raised, you don’t want to single them out as an example like a guinea pig,” Ms. Bailey said. “They’re not the expert because they’re just a student. You are the expert. They’re coming for learning from you, so you should never use them as an example unless they voluntarily give their experiences as an example.”

“[My] word is free because I feel as if sharing my experience put my feelings out in the world, where they can make a difference.” – Luis Lopez

Acknowledging people’s different identities could help students feel more comfortable talking about their experiences. Mr. Will Bladt, Associate Head of School, emphasized the importance of talking about differences.

“An element of white culture is that people are taught in many cases to not talk about difference, to not talk about things like race, class. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard anyone say ‘I don’t see different races when I talk to people. I’m colorblind.’ What that does is rob people, particularly people of color of an important part of their identity. People who have a different experience or come from a different background that aren’t able to be seen in that way,” Mr. Bladt said. “I think it’s good for people to have the opportunity to understand the full facet of what makes someone who they are.”

Expressing how people are different as well as similar can bring people closer together. Senior Surabhi Singh said that religion classes, which taught about different beliefs around the world, helped her because people were able to understand her beliefs better.

Senior Surabhi Singh’s parents are from India, and she practices Hinduism. She explained how much of a personal journey it was to face different cultures at home and at school.

“It’s made me stronger because I’ve always been in situations where I’m a minority, so just being able to embrace who I am and what I believe in,” Singh said. “That happened at a much earlier age for me because balancing the ideals at school with my Indian home presented some challenges and determining my identity.”

With classes such as religion, Singh feels like her classmates have been able to understand their differences better after they have studied her culture.

“Sometimes there’s misunderstandings, because someone might not understand what I believe in and parts of my culture, but never anything malicious, just some things that people don’t know about me,” Singh said. “But classes like Mr. Slatery’s world religions class, and just world his tory in general, have helped with things like that.”

Singh now is comfortable with her different cultural beliefs be cause she can share them.

“In places where I know I’m different, it’s not like a ‘I’m different, and I feel bad’,” Singh said. “It’s ‘I’m different, and I have all these things to share with everyone else, new perspectives, new experiences that I can share with my classmates.’”

Carlton believes that being able to discuss cultural differences at school is the first step to taking control of the situation. She at tended Meet in the Middle, a club that focuses on discussing people’s experiences and identities, last year, and found it to be beneficial.

“I got to talk to some people who I’ve never talked to, and we talked about different things,” Carlton said. “I feel like if that had happened earlier, I would have been able to make more friends back then, more close friends.”

Mr. Gibson wants students to know they can speak up, and that they truly belong.

“[The goal at the founding of St. George’s] was to create a school environment that mirrors the world, so that means people from all walks of life coming together and learning in high school,” Mr. Gibson said. “Because when you go to college, you will be surrounded by people who are from all different walks of life. And then when you enter the workforce, you will be surrounded by people from all different walks of life, and you learn to live and work together. You learn to learn together, and that makes your education more vibrant when you have people who look at the same questions you’re looking at from a different perspective. It helps you form your own opinion.”

Students said they took strength in the resilience of their communities.

Racism and racist actions are constantly being reported on by news outlets. U.S. News reported just recently that white supremacist propaganda nearly tripled just last year. Despite these events, people of color continue to bring their communities together.

In 2017, the New York Times reported on two rallies in Washington: the March for Racial Justice and the March for Black Women. The mission statement for the March for Racial Justice was to “harness the national unrest and help focus it into a national mobilization.” Many other marches like the Indigenous Peoples March in 2018 at Washington also fight for racial equality.

Bowman is proud of her race because of how they continue to come together.

“Because of all the hardships we endure like the racism and the discrimination we receive from other people for doing absolutely nothing or doing things that we have every right to do, it makes me view us as stronger,” Bowman said. “Because we go through all of that, we are still able to hold our head up high and have a positive outlook on the entire situation.”

Vann said that she hopes all people will come together as a human race.

“We all have to survive on this earth at the end of the day so why not live together?” Vann said. “Why not make it as peaceful as it can be and enjoy our time on this earth while we still have it?”