Finding a Work Around

How can students find a balance between good mental health and a healthy school life?

When junior Mary Wilkes Dunavant gets stressed, like, really stressed, it affects everything.

“My stomach hurts, and I’m so moody, like, I hate people during that time,” Dunavant said. “I feel like my life is spinning out of control because there is so much work that I have to be able to manage my time well to accomplish… I just kind of shut down for a few days and have to have a few days to pick back up and be smiley and, like, jolly in the hallways again.”

Dunavant credits her mother, a therapist, with helping her deal with her feelings of anxiety.

“She helps manage my stress, and she’ll be like, ‘it’s okay, it’s high school,’” she said. “Like, ‘if you get a bad grade, you get a bad grade. You’re smart, and we all know it.’”

While not every parent is a therapist, they still notice when their kids are stressed about school.

In 2013, NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health conducted a survey among parents to gauge the amount of school-related stress their children had experienced in the last year.

Nearly four in ten parents (38%) with children in grades 9-12, and over a third (36%) of parents

of children in grades 6-8 said their child experienced a lot of school-related stress.

Not all stress leads to diagnosed anxiety, but some does.

According to the CDC, 7.1% of children aged 3-17 years have been diagnosed with anxiety.

In 2016, National Public Radio reported that up to one in five kids living in the U.S. show signs of mental health disorders in a given year, including depression, anxiety and substance abuse. However, 80% of American children who need mental health services don’t get them.

According to the Tennessee Department of Education, untreated mental health issues can result in

a buildup of absences, and these students are the most likely to drop out of school.

For students, mental health was a problem even before the pandemic. With COVID-19, the importance of good mental stability has returned to the forefront of people’s minds.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry says that the most common stressors teens experience include school demands, taking on too many activities, over-whelming expectations, social problems/issues at school and family financial problems.

A study reported by Forbes in 2020 found that Gen-Z (people aged 6-24) spends an average of nine hours a day on their phones. The addition of social media means that it’s hard to get away from the stress, even for a short time.

“Without a doubt, social media, whether we like it or not, does play a part in affecting teenagers’ mental health,” Sophomore Grayce Thompson said. “I have found myself often comparing myself

to other people on social media, which is not healthy to do.”

She also said social media de- creases self-assurance in teens.

“This constant comparison of oneself to others makes it harder to stay positive if you keep focusing on the ‘bad parts’ about you and wishing you looked different,” Thompson said.

The feeling of depleting mental health can come from multiple factors. Some don’t meet the surface, so it can be harder to pinpoint when they begin. This is why treatment is crucial.

According to The American Psychological Association, Gen-Z is 27% more likely to report poor mental health and 37% more likely than other generations to receive treatment and/or therapy from a licensed professional.

Mrs. Emily Metz, upper school history teacher, found that this

fact is something she can back up with experiences of her own. More often than not, she believes, Gen-Z will speak up for themselves around people they trust.

“Most kids will tell you they are struggling, in my experience. This probably isn’t, you know, every teacher across the board, but most kids will say, ‘I’m freaked out right now.’ ‘I’m struggling.’… ‘I am overwhelmed by x, y, z,’” she said. “And sometimes there are tears, but crying is totally fine. That’s an acceptable response.”

Similarly, English teacher Mr. Zachary Adcock said that he trusts students who speak up about their struggles.

“I’m really proud of my students who will advocate for their mental health, actually,” he said. “My hope is that we would never use mental health as a crutch or as an excuse, but I will 100% believe you if you’re like, ‘I just couldn’t do my homework last night.’ There’s great power in self-advocacy.”

Ms. Nikki Davis, director of upper school counseling, remembers earlier generations addressing mental health differently. Counselors would do everything from college application support to testing prep to mental health support, which didn’t leave much time to focus on anything. She emphasizes how counselors in the past didn’t necessarily put mental stability as a top priority but instead gave topics such as testing more attention.

“I feel like when I was in high school, some of the things that stressed me or my peers out, we kind of had to… I don’t want to say fend for ourselves, but our counselors had a lot more to do,” she said. “I do feel like it has changed for the better, where people are more aware, and we’re making sure that we address [mental health] more.”

Mental health issues don’t go away on their own. Even in states with the best access to mental health resources, nearly one in three teens are going without treatment according to Mental Health America.

Mrs. Pam McCarthy, director of the upper school, believes that simply having a diagnosis can make

a huge difference in how students view themselves.

“I think for some students, having a diagnosis has helped them know themselves better,” she said, “It gives an explanation, if you will, for why x, y, or z is happening, and so sometimes… that’s freeing, and they’re able to think differently about their mental health.”

Being able to bounce back from mental health decline is difficult; however it can be a little easier with help. There is a 90% improvement rate for mental health issues when they are treated.

Mrs. Metz believes that diagnosis shouldn’t be something to hide. Starting an open conversation about mental health can destigmatize the diagnosis and empower people.

“I think being open and honest about mental health is super important… I’ve struggled with anxiety and depression, and my students who know are like, ‘Oh, okay. It’s okay.’ I am medicated for anxiety, and that has totally changed my life,” she said. “You are not a weak person for struggling with this. There are people in this building, and also people in the outside world, who want to help and support student mental health.”

When students feel overwhelmed, they often end up in the office of the upper school learning specialist, Dr. Brenda Monk, for academic coaching and support. Still, she aims to support the student as a whole person.

Dr. Monk serves as a guide to promote accountability for students with learning disabilities or challenges at St. George’s. She says that anxiety is something that comes into play with every student she works with.

“I would say 100% of every student that I work with, 100% of those students have some sort of anxiety or mental health [issue], in addition to [their learning differences],” she said, “so my job is to support them through letting them understand they have learning differences, and also to help them really begin to figure out on their own ways that they can cope with that anxiety, and try to diminish it.”

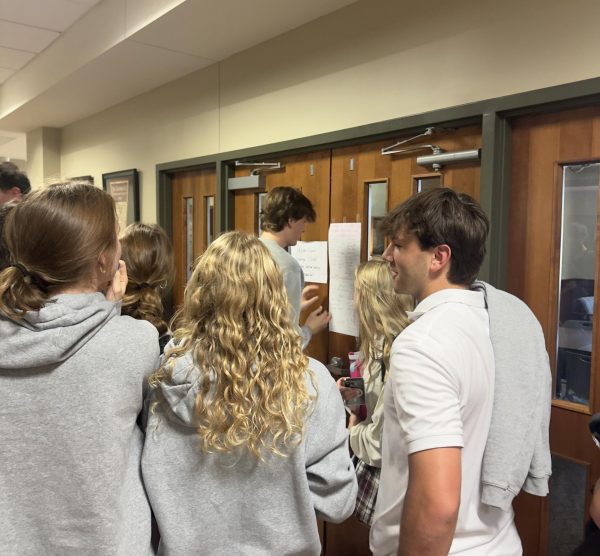

Dr. Monk also keeps an eye on “at-risk students.” Each week, an algorithm is run through Canvas to check for students with a 70% or below in one or more classes. Using this information, Dr. Monk takes time to check in with each of those students.

“I would say I would touch base with probably 100 students in a seven-day cycle,” she said.

Check-ins can keep students from getting so far behind and overwhelmed that they feel like they can’t catch up.

Mrs. Davis is also a resource for students struggling with stress and anxiety.

“I think that mental health is so important,” she said, “and it’s becoming more apparent that we need that help in high school. I really like that, in my role, I’m able to focus on that.”

Having support systems that take a direct interest in students’ mental well-being like Mrs. Davis, provide a safe haven for those that feel like they have nowhere else

to go. This is especially helpful for teachers who reach out when students are wary of beginning that conversation themselves.

“As I’ve transitioned into this role, and getting to know more of the upper school students, I’m able to kind of tell when something is going on. I’m [also] teacher-recommended,” she said. “So maybe the teacher is noticing something, or another administrator is noticing something in their classroom or in the hallway, and they reach out to me, and then I, in turn, reach out to the student.”

While reaching out for help isn’t always easy, people like Thompson have found it beneficial.

“I feel like the teachers definitely do respect, like, if you are stressed out or something, they will try to help you. Or like, extend due dates or something like that, ” she said.

With trust and support being built between staff and students, the school becomes a place where people are willing to talk about important issues and their solutions more openly and honestly.

What can students do better?

According to the Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development, a non-profit that supports educators, procrastination and time management are a significant source of stress for 55% of high school students, and 81% of students admit to multitasking when they do their homework, which can slow progress.

Dean of Students Mrs. Leanne Ricketson believes that an accumulation of work can be really challenging, but there are ways to avoid it.

“I think too much work can really really hurt people for sure, but I think sometimes people are their own worst enemy in letting that work pile up,” she said.

“I think students in general use [structured school time] really poorly and tend to procrastinate a lot and then be like, ‘I’ve got so much. I’m drowning.’ And it’s like, right, but you’ve done actually nothing in study hall for the last 10 days, so what would drowning have looked like had you chunked that out and used that time more wisely?”

Not developing good working habits in high school can become an issue later in life.

A survey conducted by Greenfield Online found that nearly half of college students feel their high school did not prepare them with the organizational skills required to do well in college.

Dr. Monk aims to ensure that St. George’s students don’t find themselves in that position once they graduate.

One of the strategies Dr. Monk suggests to students is a Pomodoro-inspired technique that uses a 20-minute timer to focus on one thing at a time, followed by a short five-minute break between focus changes. This extends the amount of work a student can get done in one sitting.

“No one should ever work on any one assignment for more than 20 minutes without a break,” she says. “You’re going to work for 20 minutes, and then you’re going to take a break, go do

something else, and then come back and study.”

Ms. Davis and Dr. Monk both said they believe that using a weekly planner can make a substantial difference in helping students develop good work habits. St. George’s provides a custom St. George’s planner to every student at the beginning of every school year.

“The cool thing about planners is you can use them as you need, like some people use them to help set goals,” Ms. Davis said. “Some people use them to be more specific about how they use their time.”

Thompson is one student who finds planners to be a work-habit wonder.

“I like to be organized, so I definitely do use my planner all the time,” she said. “[I] like to color coordinate it and make it as fun as possible because it was hard to remember everything.”

Seeing a visual such as a planner can help with overall preparedness and setting good organizational habits to help avoid a dump of last-minute work.

Mrs. McCarthy suggests that taking things one step at a time without stressing about the big picture will help students get things done in a timely manner.

“Take one step, do one thing, and just do it to the best that you can, in this moment, not the best ever, but the best that you can for now, to get it done,” she said.

Because of COVID, exams have been canceled for the last two years and the skills students acquired through the exam process may have dropped off. This year, exams are back for good.

Dunavant thinks that while exams are hard, we can learn a lot from the experience.

“Obviously, I wish we didn’t have exams,” Dunavant said, “but I do think they are going to be good just, at least for me, to learn how to study properly because I know in college that teachers aren’t going to be as lenient as they are here.”

While Dunavant believes that exams are stressful, she also said they are important to experience in high school.

“I do believe that this is the time that I’m supposed to be learning my study habits,” she said.

“I think it’s good that we’re having exams for college.

Finding a balance between providing rigorous academics that prepare students for college and tending to their emotional needs is something students say still needs work, however.

Dunavant believes that while most teachers at St. George’s do a good job understanding that there are more aspects to a student’s life than schoolwork, some don’t.

“Most of my teachers this school year are really understanding that we have other things to do in our life,” she said. “I have a job, I play soccer, and I feel like with one teacher it’s like ‘No, this class comes before anything, like, even if you’re busy, stay up two hours later to get it done.’”

Thompson agreed that, in her experience, most teachers will work with students when it comes to due dates as long as they know what’s going on in advance. Communicating with teachers is particularly important for her because she occasionally struggles to hit deadlines.

“Obviously, certain due dates can’t be pushed back or excused,” Thompson said, “but usually, if you just maybe work on it during lunch, or just get it to them by the end of the day, they’re usually pretty okay with it.

The key, teachers say, is communication.

“I think a big solution is communication and trust, on both ends of the conversation,” Ms. Metz said. “So students need to communicate and trust that their teachers do have their best interests at heart, and they will be willing to work with them.”

Mr. Adcock agreed.

“My hope is that teachers are willing to listen to their students [about their mental health],”

he said. “Even if they have that voice in their head saying, ‘this is a phase’ or ‘this is an excuse’ or whatever, that they’re able to kind of override the weight of how history hasn’t always validated mental health as something that’s important, and listen to the voice from now that’s saying, despite

all that history, we should really pay attention to it and be careful with it and be aware of it as a real thing.”

He also said that there shouldn’t be a difference between how teachers view physical health and mental health.

“At the end of the day, no teacher would bat an eye at, like, ‘Oh, you’re sick, you should stay home.’ Right? You’re physically sick, you’ve got a cold, you’re throwing up or whatever, and I think that mental health struggles are complicated, because you’re equally sick, but in a way that’s not as visible.”

Dr. Monk believes that it’s important for teachers to keep in mind that they don’t always know the full story and to be more understanding with school work as a result. The first step, she said, is to understand the student.

“You’ve got to understand the child before you can teach the child, and if you don’t understand what’s going on and recognize that, then you’re not going to help, you’re going to increase the anxiety, ” Dr. Monk said.“If teachers can just understand the child and let the child have a part in their own learning, then that would really help tremendously in the classroom.”

Having students feel like they have an adult who understands them is an important part of St. George’s goals. Mrs. McCarthy finds that students feel and do better when they have at least one teacher that they are close to.

“I think that the most important piece in all of this is making sure that every kid, every student, has

a person here at school, who they feel like they could talk to when things are great, and mediate when things are not so great.” Mrs. McCarthy said. “I think having our teachers know students well, having our adults know the students so well, helps.”

Mrs. Metz agreed.

“Every single adult in this building wants what’s best for kids” she said. “We would not be here if we didn’t.”